workwalsh.com

The work of Thomas J. Walsh

playwriting, directing, scholarship

T.J. Walsh

Thomas j. walsh

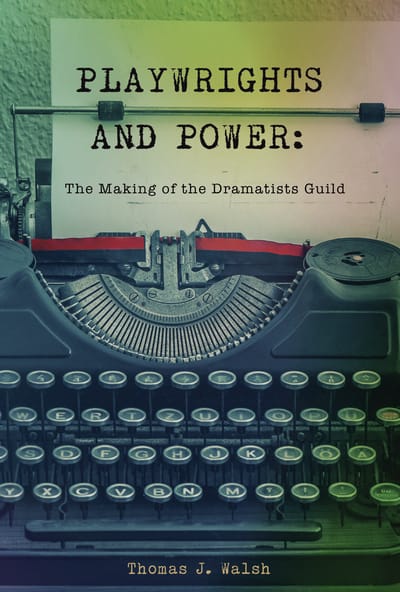

Thomas J. Walsh (T.J.) is a Professor of Theatre at Texas Christian University where he teaches theatre history, survey of theatre, playwriting, directing and acting. He is married with four children. His daughter Anna played volleyball for TCU and was first team All Big 12. She plays professional volleyball in Spain. He was the Founding Artistic Director of the Trinity Shakespeare Festival where he received four Outstanding Direction awards from the Dallas Fort Worth Theatre Critics Forum. His book: Playwrights and Power: The Making of the Dramatists Guild was published in 2016 by Smith and Kraus. His play The Thomas Paine Panther is published by Playwrights, Inc.

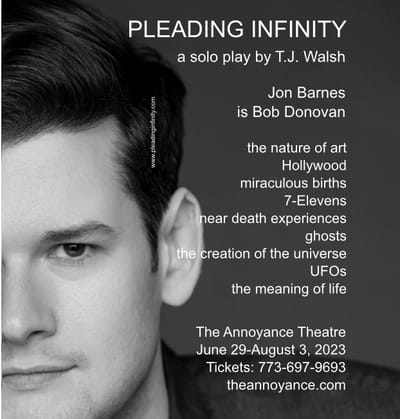

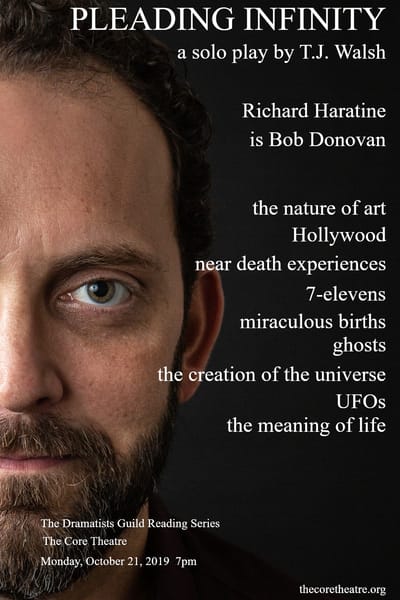

He has a Ph.D. in Theatre History and Criticism from the University of Texas at Austin where he studied with Oscar Brockett and a Master of Fine Arts in Playwriting from UT. His solo play Pleading Infinity about screenwriter Bob Donovan has been developed at the New York International Fringe Festival, The Hollywood Fringe Festival and Austin’s FronteraFest. Recently the Dramatists Guild Reading Series production of Pleading Infinity was selected by criticalrant.com as one of Dallas Fort Worth’s top ten theatrical events of the year. In the summer of 2023 Pleading Infinity ran at the Annoyance Theatre in Chicago and the Fort Worth Fringe Festival.

Three of his original plays have been produced at Texas Christian University including Melrose Stories, a character-driven comedy set in a bookstore on Melrose Avenue in LA, Born on a Sunday, an intense look at Swedish playwright August Strindberg's 1896 "inferno crisis" in Paris, and Tom Kellogg in B Flat, a romantic comedy made up of four one-act plays set in the 1980s chronicling the adventures of the title character. Two monologues from Tom Kellogg were published by Smith and Kraus in Best Monologues of 2020.

He is a member of the Dramatists Guild of America.

He can be reached at t.walsh@tcu.edu.

He has a Ph.D. in Theatre History and Criticism from the University of Texas at Austin where he studied with Oscar Brockett and a Master of Fine Arts in Playwriting from UT. His solo play Pleading Infinity about screenwriter Bob Donovan has been developed at the New York International Fringe Festival, The Hollywood Fringe Festival and Austin’s FronteraFest. Recently the Dramatists Guild Reading Series production of Pleading Infinity was selected by criticalrant.com as one of Dallas Fort Worth’s top ten theatrical events of the year. In the summer of 2023 Pleading Infinity ran at the Annoyance Theatre in Chicago and the Fort Worth Fringe Festival.

Three of his original plays have been produced at Texas Christian University including Melrose Stories, a character-driven comedy set in a bookstore on Melrose Avenue in LA, Born on a Sunday, an intense look at Swedish playwright August Strindberg's 1896 "inferno crisis" in Paris, and Tom Kellogg in B Flat, a romantic comedy made up of four one-act plays set in the 1980s chronicling the adventures of the title character. Two monologues from Tom Kellogg were published by Smith and Kraus in Best Monologues of 2020.

He is a member of the Dramatists Guild of America.

He can be reached at t.walsh@tcu.edu.

contact

Comments and questions welcome. If you are interested in producing T.J. Walsh's work as a playwright, in contacting him to direct or in bringing him in as a speaker please contact him. *Photos by Amy Peterson

playwriting

"As [Pleading Infinity] progresses, the emotional arc of Bob's journey moves to the fore. This is Walsh's real accomplishment as a playwright and story teller, and is all the more remarkable for the subtlety with which it occurs." Todd Carlstrom, nytheatre.com

"Born on a Sunday is an amazing accomplishment in and of itself, but the fact that Walsh is able to fashion a production of such superior quality with non-professional actors in training is mind blowing." M.Lance Lusk, D Magazine

"Mr. Walsh has looked past recent romantic comedies for models and gone straight to the top. The juxtaposition of low popular humor with serious characters and situations feels Shakespearean, in a nicely unpretentious way. The laughs are there, and the deeper emotions as well...Melrose Stories is a real contribution to the vanishing genre of romantic comedy." Lawson Taitte, Dallas Morning News

BORN ON A SUNDAY

Theater Review: Proving August Strindberg’s Greatness

D Magazine

By M. Lance Lusk Published in Arts & Entertainment

I am always saying I would like to see more plays by August Strindberg. His experiments in expressionist and surrealist techniques and dream-like Scandinavian moodiness are beyond intoxicating to this critic. Now, the chance to see an original work about that incomparable Swede, done in his distinctive style by an incredible director and playwright was a theatrical blessing. Theatre TCU presents Born on a Sunday written and directed by T.J. Walsh.

There is a reason Eugene O’Neill referred to Strindberg in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech as “that greatest genius of all modern dramatists.” He was an exceedingly prolific polymath playwright, poet, essayist, novelist, painter, and dabbler in the sciences. However, he experienced a tumultuous time of psychotic attacks, paranoia, delusions, and religious turmoil while he was abroad in Paris in the 1890s called the “Inferno crisis.”

The program notes inform the audience that much of what we are seeing is “true…the rest is imagination.” And that is the special genius of Walsh’s play, that investigation of this crucial time in Strindberg’s life seen through a speculative lens that resembles his visionary experiences that straddle the real and dream worlds. From Brian Clinnin’s whimsical, bridge-like set of wood beams, rivets, curves, and elevated platforms, to the clear, fantastical, and chilling sound design and composition, and lights by Chris Hassler and Jim Rogers respectively, to Yuheng Dai’s luxurious period frock coats, gowns, and Victorian-inspired dance outfits this is a play that sets a definite mood of history and reverie.

Walsh, an Associate Professor of Theatre at TCU, is also the co-founder and Artistic Director of the excellent Trinity Shakespeare Festival. Born on a Sunday is an amazing accomplishment in and of itself, but the fact that Walsh is able to fashion a production of such superior quality with non-professional actors in training is mind blowing. They handle this difficult and unconventional material with artistic ease.

Standouts from this excellent ensemble include Bradley Gosnell as the tortured Strindberg, Gabriel Whitehurst as Dr. Horatio Christensen, the Danish psychologist who befriends and treats the playwright with hypnosis, and Shae Lynn Goldston as a fiery feminist doctor in love with Horatio. A special note of recognition too for the sylphlike Furies/Muses (Marisa Bonahoom, Caroline Iliff, Jackie Raye, Abbie Ruff, Lexie Showalter, Kelsey Summers, and Zach Gamet as The Power) who plague and inspire Strindberg. Choreography by Penny Ayn Maas contributes to this chilling ballet of intertwined and inspired madness.

Strindberg craving fulfilled.

PLEADING INFINITY: a solo play

New York International Fringe Festival

Hollywood Fringe Festival

Dramatists Guild Reading Series

Chicago's The Annoyance Theatre

Fort Worth Fringe Festival

PLEADING INFINITY by T.J. Walsh - nominated for five Broadway World - Chicago awards!

The Annoyance Theatre

Voting has begun for the "Broadway World - Chicago" Awards

"Pleading Infinity" is nominated in five (5) categories

1. Best Play - "Pleading Infinity"

2. Best New Play or Musical - "Pleading Infinity"

3. Best Performer in a Play - Jon Barnes "Pleading Infinity"

4. Best Director - T.J. Walsh "Pleading Infinity"

5. Best Cabaret/Concert/Solo Performance - Jon Barnes "Pleading Infinity"

ONLINE REVIEW:

"I attended the June 29 performance of "Pleading Infinity". I am not normally a fan of "one-person shows" - but this production of "Pleading Infinity" is VERY, VERY IMPRESSIVE! I enjoyed the way the script is structured ... and the dialogue is well-written. Combine that conversational dialogue with the exceptional performance of Jon Barnes - - - and this is a wonderful, FIRST-RATE PRODUCTION definitely worthy of Joseph Jefferson Award consideration. Mr. Barnes' performance was truly so believable, I never thought he was reading a script. I thought he was telling "HIS STORY" to us. There shouldn't be an empty chair in the Small Theatre."

* * * *

nytheatre.com review

reviewed by Todd Carlstrom · NY International Fringe Festival

I'm going to be frank: seeing a one-person show makes me worried. It's more of an all-or-nothing proposition than a multi-character offering, simply because I'm charging one single person with my evening's entertainment. Fortunately, in the six monologues that comprise Pleading Infinity, T.J. Walsh proves himself eminently worthy of such responsibility.

As Bob reveals details about his family life, both as a child and now as a husband and father, his priorities come into focus, and an unexpected tenderness emerges gracefully from the script. His gradual transformation from thoughtless cynicism to spiritual self-realization happens (super)naturally, never seeming forced.

As the show progresses, the emotional arc of Bob's journey moves to the fore. This is Walsh's real accomplishment as a playwright and story teller, and is all the more remarkable for the subtlety with which it occurs.

* * * *

Dallas, Texas

criticalrant.com

Theatre Reviews & Perspectives:

Reflect, Intersect, Inspire

by Alexandra Bonifield

Pleading Infinity: a solo play

My final two notables of 2019 are workshop stagings of works that demonstrate much promise.... Back into the solo actor realm, regional playwright and author, professional stage director and TCU theatre professor Thomas J. Walsh brought his spooky yet poignant PLEADING INFINITY to Richardson’s Core Theatre, as part of The Dramatist Guild Reading Series. The quirky, engaging show featured veteran actor and Texas Wesleyan professor Richard Haratine. Negotiating plot twists reminiscent of The Twilight Zone, the solo actor plays a screenwriter revealing conversationally his life experiences relating to Hollywood, near death moments, birth, ghostly haunting, UFO visitation, the nature of art and the universe’s emergence. Beautifully crafted as a literary work and acted equally well, the show provides intrigue and charm as it glides towards completion as a work. It’s had other [performances in Fort Worth, Los Angeles and New York City]. Superior script by Walsh meets sterling performance by Haratine. Hope for a full regional mounting in 2020. The Core Theatre, Richardson TX

MELROSE STORIES

"Melrose Stories is a real contribution to the vanishing genre of romantic comedy." Lawson Taitte, Dallas Morning News

Short from the TCU Production: https://youtu.be/YAx4PDx38HY

A video of the TCU Production: https://youtu.be/hjfmeGCygg8

MELROSE STORIES by T.J. Walsh

TCU's 'Stories' has happy ending in this romantic comedy

LOVE AND LAUGHS CONQUER ALL OBSTACLES IN ADVENTUROUS COMEDY

Dallas Morning News

by Lawson Taitte, Theatre Critic

Melrose Stories has two strikes against it, right from the start. The hero narrates the story by talking to the audience. A lot. And the character is a writer - seldom a good sign.

But no inning is over until the final out, and playwright T.J. Walsh keeps swinging hard and gets a hit - maybe not a home run but definitely a triple.

Texas Christian University, where Mr. Walsh teaches, gave Melrose Stories its world premiere Wednesday under the playwright's direction. This romantic comedy dares a lot. Its tone ranges from sitcom humor to a magical ending right out of Jacobean romance. And it baldly lets you know it's doing just that. A beneficent ghost wanders through the action, and the plot involves a big secret. (The savvy will guess it immediately, yet the answer still feels unprepared for when it comes out - just as Mr. Walsh planned.)

The action mostly takes place in a Los Angeles bookstore, though it also wanders freely through space and time. The narrator, a New York novelist named T.D. Kellogg (Clint Gage), has been suffering from writer's block for more than a decade after his successful debut. His aunt (Katie O'Brien) dies and leaves him her heavily mortgaged store. T.D. falls in love with the place, the staff and - in a romantic way - the manager, Rose (Michelle Martinez).

The scenes in the store do feel a lot like high-quality TV comedy, with the employees and regulars trading quips and exuding hormones. Mr. Walsh halts objections by having the funny guy, Walter (C.J. Meeks), quarrel endlessly with Wilma (Jaclyn Napier), a feminist grad student who's writing her thesis on sitcoms.

Mr. Walsh has looked past recent romantic comedies for models and gone straight to the top. The juxtaposition of low popular humor with serious characters and situations feels Shakespearean, in a nicely unpretentious way. The laughs are there, and the deeper emotions as well.

Perhaps the mystical happy ending doesn't have quite the tearful payoff it should - but it could just be that the student actors aren't always the right age or in possession of enough technique to make the improbable convincing.

A number of cast members are outstanding anyway. Ms. O'Brien radiates the right kind of hopeful aura, Mr. Meeks is hilarious, and Scott Rickels as the gay store employee has a nice offhand charm.

Melrose Stories is a real contribution to the vanishing genre of romantic comedy.

TOM KELLOGG IN B FLAT

a romantic comedy

W A T C H:

A youtube short scene from the TCU production "The Kiss":

https://youtu.be/9bDSzoJugjA

A youtube look at the production at TCU:

https://youtu.be/R405cT2an6U

In this touching and very funny comedy prequel to Melrose Stories we see young Tom Kellogg living in his San Francisco flat in the 1980s trying to sort out the complexities that have become his life. The play is four different scenes set in Tom's flat leading to major decisions in his life.

In the first story A PAS DE DEUX IN REMEMBRANCE we see Tom having to contend with a former lover, Jane, a dancer for the San Francisco Ballet, whom he still loves. In the second story A SEMINAR IN B FLAT, we find a graduate student from Columbia University who shows up for an early morning interview with Tom about his books but she really is more interested in his private life (and Jane) that are suggested in his books. In the third story AT RISE, we find Tom awake at 3am being confronted by his live-in girlfriend, Irene, an actress who is starring in a new play he has written, who is up and reading one of his books that happens to be about Jane. And finally in the fourth play, MAKE BELIEVE BALLROOM, Tom has a comic but moving heart-to-heart with his best friend, Joe, about the women in his life and his next step - to head out to New York City (where Jane has moved).

This is a funny and touching comedy. The four plays work brilliantly as an evening or each can stand up as a one-act of their own.

Single Set

5 Characters

3 women, 2 men

the thomas paine panther

Playscripts, Inc. Publishers

https://blog.playscripts.com/play/566

30 - 40 minutes

4 f, 4 m

Set: Unit set.

Set during the AIDS crisis. The student staff of the Thomas Paine High School newspaper has been banned from publishing their annual "Best/Worst" issue, but their headstrong editor is determined to go ahead with it. Mr. Smith, the paper's sponsor, discovers what the students are up to just as they learn a shocking secret about him -- and this triggers a high-stakes confrontation on ethics, journalism, and the rules of being a teacher and friend.

Photos from the First Colonial High School production directed by Zack Kattwinkel:

Presented at both the Virginia Thespian Festival and the Virginia High School League Class 5A Sectionals. FCHS received the following accolades:

- Best "Truth in the World" Award at Thespian Festival (an important theme or idea with relevance to the audience)

- 3rd Place and Overall Rating of "Excellent" at VHSL

- Outstanding Performance Awards for Elijah Gumm (Mr. Smith) at both

- Outstanding Performance Awards for Calix Kimel (Kirk Mayer) at both

- Outstanding Performance Award for Charlye Levine (Heather) at VTF

- Outstanding Performance Award for Lex Shoemaker (Karen) at VTF

- Outstanding Performance Award for Axel Sifuentes (Anzo - Alma) at VHSL

edwin booth: to thine own self

EDWIN BOOTH: TO THINE OWN SELF

by T.J. Walsh

Commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth

video from Amon Carter presentation:

https://youtu.be/lLiEveppVJM

PROFESSIONAL DIRECTING

trinity shakespeare festival

Artistic Director

A summer professional Equity company housed on the campus of Texas Christian University: 2009-2018.

Directing one play per summer.

"T.J. Walsh directs Shakespeare with a defining, comprehensive understanding of the works and unwavering affection for them. He solves the challenges inherent in the so-called “Problem Plays” as if they are child’s games. Last year’s production of The Winter’s Tale, an odd mix of performance styles with a convoluted plot, hateful characters, a man eaten by a bear, a pastorale and the surreal transformation of a statue to life became a poignant love poem of redemption and reconciliation under Walsh’s tender, clearly delineated guidance. So it goes with this year’s production of the problematic Measure For Measure." Alexandra Bonifield, criticalrant.com

some Trinity Shakespeare Promos:

2016 Season Promo: https://vimeo.com/256311591

A Midsummer Nights Dream: https://vimeo.com/256311455

A summer professional Equity company housed on the campus of Texas Christian University: 2009-2018.

Directing one play per summer.

"T.J. Walsh directs Shakespeare with a defining, comprehensive understanding of the works and unwavering affection for them. He solves the challenges inherent in the so-called “Problem Plays” as if they are child’s games. Last year’s production of The Winter’s Tale, an odd mix of performance styles with a convoluted plot, hateful characters, a man eaten by a bear, a pastorale and the surreal transformation of a statue to life became a poignant love poem of redemption and reconciliation under Walsh’s tender, clearly delineated guidance. So it goes with this year’s production of the problematic Measure For Measure." Alexandra Bonifield, criticalrant.com

some Trinity Shakespeare Promos:

2016 Season Promo: https://vimeo.com/256311591

A Midsummer Nights Dream: https://vimeo.com/256311455

twelfth night

directed by T.J. Walsh*

Trinity Shakespeare Festival

*Outstanding Direction Award, DFW Theatre Critics Circle

BRING IT ON! TRINITY SHAKESPEARE

Dallas Morning News

by Lawson Taitte

It’s time to leap for joy, fans of classical theatre. This past week Fort Worth’s revitalized Trinity Shakespeare Festival sprang forth fully formed, like Athena from the head of Zeus. It’s a bold birth, ready to make dynamic artistic statements and enliven the words of Western culture’s leading playwright with a vision that connects the Bard’s texts to the modern world. Under the guidance of T.J. Walsh and Harry B. Parker, the 2009 Festival employs two Texas Christian University venues to present combined professional/ student staffed and cast productions of comedy Twelfth Night and tragedy Romeo and Juliet. They both do admirable justice to the plays and provide high caliber entertainment to full house audiences. No tentative rebirth!

You won’t encounter more masterfully designed, exquisitely beautiful or performance enhancing sets at any regional venue. Twelfth Night, designed by TCU professor and union designer Michael Heil, with credentials ranging across the US, Europe and Asia, creates lyrical magical surrealism on the proscenium-style Buschman Theatre at Landreth Hall. A massive rectangular panel floats upstage at the back of the uncluttered playing space, painted in rich Mediterranean hues to look like sky. It presides over all action and opens up the space with clean linear definition. While clearly man-made, it constantly reminds the audience of the setting’s proximity to nature and the play’s contrasting themes of artifice and truth. Fanciful, stylized, Styrofoam trees frame the playing space and reinforce the clean Mondrian-like linearity of the overall design. Readily movable elements, the actors use these trees to enhance the humor of particular scenes. Like the free-floating sky painting panel, the trees visually reinforce the contrast between the artificial and the real throughout the play. All other set elements are simple and uncomplicated, either carried in and out by actors or softly flown in from above. A whimsical triumph, takes the breath away.

Under Walsh's direction it is David Coffee’s show as he croons and intones composer Martin Desjardins songs as the court clown Feste. He comes across as part conjurer/ part madman, seems to spin the illusionary tale of romance and mistaken identity. Secondary characters dominate the stage, from J. Brent Alford as irreverent drunk Sir Toby Belch to scheming, lusty Emily Gray as Maria, to indefatigable Daniel Frederick, clearly favored by the audience, who makes a completely geeky donkey of himself with reckless, joyful abandon any time he strides on stage. David Fluitt creates an unforgettable, suffering steward Malvolio, Shakespeare’s satirical depiction of the Puritan opportunists running amok at Elizabeth I’s court at the time. (Stephen Colbert has nothing on the Bard in the way of incisive character assassination.) Trisha Miller Smith has some lovely moments as Countess in mourning Olivia.

Welcome back to life, Trinity Shakespeare. You’re needed; your aspirations and accomplishments are honorable. I’m delighted to see such enthusiastic, engaged audiences. Bring it on!

hamlet

directed by T.J. Walsh

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

"While there may be plenty of things rotten in Denmark, there is nothing foul about the Trinity Shakespeare Festival production of Hamlet. This solid-as-a-rock presentation of one of the best-known Shakespearean tragedies directed skillfully by T.J. Walsh lets the text tell the story. Punch Shaw, Fort Worth Star-Telegram

* * * *

"Director T.J. Walsh freshens up what has become too conventional in most productions, allowing his actors to deliver their lines, no matter how famous, as whispered asides or up-tempo pronouncements. Turning an innovative eye on a classic while maintaining its timeless magnitude is no easy feat." M. Lance Lusk, theaterjones.com

* * * *

"In the thrust configuation of the Hays Theatre, the audience can hear every word with no need for amplification. Brian Clinnin's set, Michael Skinner's lighting and Ric Dreumont Leal's costumes create an early Renaissance vision in russets and browns. The ghost scenes directed by Mr. Walsh are spooky and fantastic." Lawson Taitte, Dallas Morning News

* * * *

"The vigorous and commanding Andrew Milbourn fulfills one of the most challenging and sought-after roles in all of Shakespeare with fresh and daring aplomb." Alexandra Bonifield, criticalrant.com

As you like it

directed by T.J. Walsh

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

youtube trailer: https://youtu.be/cYrpvMzGYlo

D Magazine

Theater Review: Why Trinity Shakespeare Festival Delivers the Best Bard You’ll See in North Texas

By M. Lance Lusk

Only three years into its short existence, and yet again, Trinity Shakespeare Festival continues to provide by far the best of the Bard’s work in Dallas-Fort Worth. After receiving funding from TCU for two years, they are now on their own, yet the quality is not diminished a whit as they take audiences on two disparate, yet glorious journeys in As You Like It and Macbeth.

Director T.J. Walsh, of the critically lauded Twelfth Night and Hamlet for the festival, delivers simply the most transcendent, heartfelt and clarion productions of As You Like It you are likely to see, from the inspired casting, the passionate and nuanced performances, to the beautifully simple aesthetics of the play.

The story of would-be lovers Orlando (Jonathan Brooks doing his youthful best) and Rosalind (Trisha Miller), among others, fleeing danger to the idyllic forest of Arden is merely a pretence to the many other wonders of this most theatrical of Shakespeare’s comedies.

Walsh plays up that theatricality in having the “All the world’s a stage” speech begin the play on a striking set (Clare Floyd DeVries) dominated by tall, soaring tree trunks that remain in and out of the forest scenes.

The play is quite the charmer already, however, its success hinges on the most vital of all of Shakespeare’s comedic heroines: Rosalind. The husky-voiced Miller (splendid in last year’s Much Ado) is lovely and exuberant, and blooms in her boyish weeds with a lively intellect to match. David Coffee’s Touchstone, a clown in Rosalind’s retinue, is a clever mash-up of W.C. Fields and the Mad Hatter using the patented squinty “Coffee Face,” and a thousand actorly gestures and quirks. Jakie Cabe as Jaques (recently brilliant in Theatre Three’s Travesties) is a gentleman of a ripe, sullen disposition who wallows in his melancholy with excitement.

Aaron Patrick Turner’s Edwardian costumes are a feast for the eyes, and jibe well with the vision of the courtly vs. the pastoral. Kudos for his work on the Scottish play as well.

Thank goodness Walsh is able to elicit such genuine, yet studied performances that capture that elusive and quintessential Shakespearean quality of characters overhearing themselves as if really thinking out loud.

THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR

directed by T.J. Walsh

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

D Magazine

by M. Lance Lusk

Now in its fourth season, the oft-loved and critically-acclaimed Trinity Shakespeare Festival presents a comedy, Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor, that is a little unconventional in that it is set entirely in England with no single, definitive source, and it centers on the middle-classed folks of Windsor (no kings, queens, or dukes here). Even though, as a farce, it is well-constructed and fast-moving, the play has always felt a little forced. And it certainly presents a far inferior Falstaff to the one living in the Henriad.

That is, until now. What a beautiful treat it is to rediscover a popular play when it is done in such a straight-forward way. That’s what Trinity Shakespeare Festival achieves with its complete and colorful new production, and in the process, the Fort Worth summer festival reaffirms its theatrical dominance once more.

The dead simple plot follows Sir John Falstaff (David Coffee), woefully short on funds, as he schemes to make amorous overtures to the steadfast wives (Lydia Mackay as Mistress Page and Trisha Miller as Mistress Ford, both wry in all the right spots) and Messrs, Ford and Page (Richard Haratine and J. Brent Alford respectively). Mistress Page’s daughter, Anne (a fresh and earnest Amber Marie Flores), is also the object of desire of three would-be suitors: a fancy fool named Slender (the studied, point-perfect G. David Trosko), the oh-so-French doctor Caius (an over-the-top awesome Blake Hackler), and the heartsick young’un named Fenton (Bradley Gosnell). Each of these men asks for the assistance of Mistress Quickly (a delightfully slummy Amber Quinn). Throw in an eccentric Welsh parson, Sir Hugh Evans (Chuck Huber wielding an impressive accent), and assorted other colorful characters, and you have an enchanting menagerie of merriment.

Trinity stalwart Coffee reprises the role of the fat knight to great effect here with jumping eyebrows over his omnipresent squint, and with his expansive frivolity. It is not often that this faux Falstaff can shine in this light as meringue ensemble piece that features a Sir John who does not measure up to the humorous and insightful knight in his other plays. Tradition holds, perhaps apocryphal, that Queen Elizabeth commissioned Shakespeare to revive the beloved Falstaff in a new play and to show him in love. However, such is the brilliance of festival Artistic Director T.J. Walsh (last year’s delightful As You Like It), who has a jeweler’s eye for the material, that he is able to elicit transcendent performances from his actors, and present a fully realized world for them to inhabit.

Another standout performance is the ever-charming Miller (one of my all-time favorite Rosalinds), as Mistress Ford, who luxuriates in every purred line of dialogue. Still, the show nearly belongs to Richard Haratine (last year’s swashbuckling Macbeth) who is a thorough, scene-stealing hoot as the jealous, moneyed “knave” of a husband. He is almost funnier than Falstaff, and that’s saying a lot.

The production features great performances all-around, because they are full characters and not just the capital “S” Shakespeare cardboard cutouts so often put on stage, where you mostly see the strain of maintaining the iambic pentameter and not the acting.

The aesthetics of the play are stunning too. Leigh Ann Chermack’s sumptuous costumes, Sean Urbantke’s beautiful bucolic set that works with clockwork precision, and Tristan Decker’s illuminating lighting complete the picture.

The takeaway: we can discover great things even in a supposed middling play if it’s done the right way, and Trinity is making quite the impressive habit of doing just that.

the taming of the shrew

directed by T.J. Walsh*

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

*Outstanding Direction Award, DFW Theatre Critics Circle

youtube trailer: https://youtu.be/cRb4iaVMRoo

D Magazine

by M. Lance Lusk

Upon hearing that Trinity Shakespeare Festival was opening with The Taming of the Shrew, I was more than a little underwhelmed. Shakespeare’s sometimes-popular, farcical comedy has become relegated to either distant source material for the musical Kiss Me Kate or the record of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton’s torrid marriage writ large in Zeffirelli’s film. And though it is rarely staged, when the play does get produced, more often than not interpretations turn it into a relic fought over in the gender politics war.

But this is the Trinity Shakespeare Festival, which has already proven itself more than capable of handling the Bard’s trickier plays. In 2010, the festival has mounted a definitive version of the overplayed and little understood Much Ado About Nothing (directed by Stephen Fried), and last year’s the festival offered a revitalizing take on the oft-dismissed The Merry Wives of Windsor (directed by T.J. Walsh). They know what they are doing with any kind of Shakespeare over there, and boy does it show with this play.

Artistic Director Walsh helms a production that is impeccably paced, features razor sharp performances and possesses an intricate, yet charming sensibility. The world he creates with his staging meets the colorful, layered set by Tristan Decker (a 1900 Italian neighborhood), and Aaron Patrick DeClerk’s period costumes. David Coffee opens the play singing “’O sole mio” and delivers a winking prologue to the frequently discarded Induction that sets up the play-within-the-play aspect of Katherine and Petruchio’s rocky courtship. Coffee gets in a plug for Trinity’s other repertory show Julius Caesar, and sets Shrew’s “mirth and merriment” tone.

Incredible ensemble performances are typical of Trinity shows, and this play is no exception. Alex Organ as Lucentio and G. David Trosko as his witty servant Tranio are worth the price of admission alone. They caper about in disguises and relish every syllable of their lines. Organ is a real gem of local theater, and Trosko more than holds his own alongside him. Chuck Huber’s Petruchio is an affable rascal who anchors the play’s smirking yet loveable sensibility. Trisha Miller, as the spitting wildcat Katherine, is also a delight. Her catty sis chemistry with Jenny Ledel’s Bianca is a hoot. She absolutely crushes the crucial “Thy husband is thy lord” speech at the end of the play.

Coffee (playing Grumio) is so dependably good in everything that he does that one is almost tempted to become desensitized to his full-body antics and facial expressions; however, such is his talent and charm that he never fails to surprise and entertain. Alan Shorter’s music supervision is both aptly joyous and melancholy. Lovely singing by both Coffee and Amber Marie Flores is particularly good.

Five years ago Walsh wrote that Trinity’s mission was to “produce the work of Shakespeare with clarity, creativity and conscience” and allow his stories to play out with a “joy in the story-telling, a beauty in the execution and a respect for the tradition of Shakespeare’s enduring plays.” That respect for the tradition and Walsh’s vision have remained intact.

THE TEMPEST

directed by T.J. Walsh

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

criticalrant.com

by Alexandra Bonifield

AESTHETIC — noun: A guiding principle in matters of artistic beauty and taste; artistic sensibility. An underlying principle, a set of principles, or a view often manifested by outward appearances or style of behavior.

Nearly all theatre companies in this region function with mission statements, action plans of a sort, some better crafted, better articulated and better adhered to than others. Few in this region seem to have a genuine aesthetic, a “sensibility and guiding principle”, one that reaches much beyond “get butts in the seats”. While focused on doing good work for the public good and making it pay, please don’t forget to build a unifying aesthetic. Every year in June Trinity Shakespeare Festival springs to life on the campus of Texas Christian University in Fort Worth…a noisy, ambitious, energetic, hopeful version of Brigadoon. Every one of six years now, I have welcomed its emergence from the mists of creativity, scholarly rigor and rigorous craft mastery. Every year one show elevates my understanding of another Shakespeare play to a new level of delighted appreciation while the second production entertains me. I trust T.J. Walsh and his worthy creative team. They possess a palpable, definable aesthetic that permeates both productions, no matter the caliber of execution.

“The rarer action is in virtue than vengeance.” Prospero, The Tempest

In 2014, T.J. Walsh took on the challenge of directing The Tempest, beloved by many (including me), Shakespeare’s Swan Song to the theatre. Nobody interprets text with more thorough comprehension than Walsh does. He can transform entire scenes based on the different use of just one word or phrase, giving fresh, unexpected perspective to a performance. Here his talents shine. The Tempest, with its initial tsunami of a storm and parade of otherworldly creatures and unusual people, often gets presented as a fantasy spectacle with scads of over-acted buffoonery, a tad of innocent, but trite, romance and a sprawling wealth of overdone, elaborate set design. The play gets lost behind the spectacle circus act, except for a few key speeches. Trinity Shakespeare Festival’s The Tempest is the regional Shakespeare hit of the season, set against a constellation-filled sky that soars splendidly to the heavens in the Marlene and Spencer Hays black box theatre (scenic design by Sean Urbantke, lighting Michael Skinner, sound Toby Jaguar Algyar). Simple, elegant, focused yet unhurried, uncluttered, grand in universal scope yet intimately personal – it’s a metaphorical journey of enlightenment, a dharmic meditation for all on the play’s life path. The banished, embittered Prospero has created a chaotic world of disunity, as if he were following a principle of adharma. Everyone on his island, from his gentle, loving spirit muse Ariel to the Duke who banished him wrongly from Naples, to the unhappy “monster” Caliban, are little more than despairing prisoners of his will, tools locked up in confusion, resentment and misapprehension. It’s not until Prospero’s daughter Miranda falls openly, honestly in love with the young prince Ferdinand that her father strands on the island and treats as an orphaned servant that Prospero recognizes the cruel error of the revenge-driven world he has manifested with evil magic and sets all on the path to harmony and love. The transformation effected on every character by play’s end ricochets throughout the audience with heartfelt resonance and transformational release. Shakespeare was more likely a closeted Catholic than a Buddhist, certainly; yet his genius explored many ways of being. This is the most uncomplicated, loving production of The Tempest I have yet seen. As Prospero, J. Brent Alford brings his masterful ease with the complex language and depth of character development into full play and earns the audience’s teary devotion. He lives every step of the arc of transformation from adharma to dharma. Bradley Gosnell and Alyssa Robbins make an evenly balanced Ferdinand and Miranda, sensual, measured inspiration to the joys of innocent love. The Mutt and Jeff world of Richard Haratine as Stephano and Jakie Cabe as Trinculo resonates with eye-roll inspiring hijinks, with the more serious realities of Prospero’s contemporaries Alonso and Antonio in weighty counterbalance (Alex Chrestopoulos and Chris Hury). Kelsey Milbourn makes a divinely beautiful, yet tortured Ariel, as light on her feet as a falcon’s feather yet weighted down with sorrow due to Prospero’s dis-unifying manipulation.

I was amazed to see David Coffee playing Caliban, both a physically and mentally challenging role. He so completely embodied the hunched over, hostile slave-spirit I forgot it was Coffee acting, and all preconceptions of Caliban’s embodiment slipped from my mind. His final transformation to a clear-visaged, erect standing free man of dignity was one of those “special” ecstatic theatre moments a critic longs for but doesn’t always witness. Director Walsh knew exactly what he was doing in casting Coffee in this challenging role and where he was taking him to fully illustrate Shakespeare’s text. Namaste.

KING LEAR

directed by T.J. Walsh

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

TO BE CLEAR: It's all about clarity at Trinity Shakespeare Festival, where repertory productions of King Lear and Love's Labour's Lost play beautifully together.

theaterjones.com

by David Novinski

If you were looking to copy a successful Shakespeare festival, Trinity Shakespeare would be a good place to start. Just don’t expect for them to make it look easy.

Running in rep means recycling the same actors between two different shows. For some theaters that means recycling the designers, the venue and possibly the director, as well, but not at Trinity.

King Lear, directed with pristine clarity by T.J. Walsh, inhabits the Jerita Foley Buschman Theatre while Love’s Labour’s Lost, directed with comedic flare by Joel Ferrell, sits practically across the hall, fully fledged in the Marlene and Spencer Hays Theatre. These are mammoth productions with their own individual design teams, with the exception of sound designer Toby Jaguar Algya, who does double duty.

This ostentatious show of effort (especially evident in the costumes) wouldn’t be worth a hill of doublets, though, if it bogged down the Bard. Fortunately, that’s where Trinity gets it right where others just get left: clarity. Make Shakespeare accessible and the people will come.

Admittedly, the set designs do have their own flights of fancy. Bob Lavallee’s set for Love’s Labor’s Lost is a sumptuous vibrant tapestry that covers the floor and becomes the wall with tree trunk cutouts to create the forest, and Brian Clinnin’s set for King Lear has a raked stage with a backdrop of distracting seismographic squiggles. But, the clarity of the staging creates a real world the audience can enter easily.

Walsh’s opening scene of King Lear is a perfect example of the sensitive treatment an audience can expect. The beginning of the tragedy comes when the King asks his daughters to pronounce to the court which of them loves him the most. When the youngest daughter is unwilling or unable to satisfy the monarch’s demands, she’s disinherited dramatically. To a high school student reading Shakespeare’s words on the page, this comes across as the harsh behavior of kings who make their decisions through a remote and impenetrable logic.

In Walsh’s production, the throne is turned so that we are practically watching over his shoulder. Immediately, there is an intimacy that no textbook could convey. Add to that the ever-congenial David Coffee as a warm Lear and Trinity Shakes is on its way to undo years of boring English classes.

When Delaney Milbourn, as youngest daughter Cordelia, fails in her public praise, Coffee stands and closes the distance to her to give her a little private fatherly coaching before returning to his kingly seat. By turning the throne room sideways we are privy to the tender moment. Walsh’s staging makes use of the oft-neglected distinction between public and private speech Shakespeare weaves throughout his work to create a more loveable Lear. For the rest of the play the lengths loyal characters like Kent (played with an agile accent by Richard Haratine) and Gloucester (played with heart-tugging nobility by Chamblee Ferguson) go through for his sake seem reasonable in light of this opening scene. When they say that he was a great man, we don’t have to just take their word for it. We’ve seen proof.

Words can be false, after all.

The sisters Goneril (Lydia Mackay) and Regan (Sarah Rutan) are the first to thrive through empty words. Their pronouncements of love are so convincing that it makes their later treachery jarring. But two-faced characters shouldn’t shock after the subplot-summing soliloquies of Edmund (Montgomery Sutton).

The illegitimate son of Gloucester sets out in detail how he will use forged letters and lies to overthrow his brother Edgar (Bradley Gosnell). As his plots succeed no one is safe, even the two-faced sisters. When the wheel of tragedy makes its inevitable way around, the conclusion is, of course, sad, but the way the web of treachery ensnares the perpetrators makes it also satisfying.

On the balance, the audience leaves with a surprising sense of resolve. It’s an evening of high tragedy that isn’t shattering; a Lear that quivers the lip but leaves it stiff. That’s a rare achievement.

There are quibbles, of course.

The aforementioned set backdrop of squiggles and Michael Skinner’s lights, beaming through thick haze, can sometimes distract. Algya’s multi-layered storm also battles the players for attention at times. Aaron Patrick DeClerk's costumes make up for any design shortcomings, in amount and intricacy, at least, and also surprisingly subtle palettes. It’s only because of the moments when all the elements are working perfectly that draw attention to the times when they are out of sync, like all the signal lights in a turn lane flashing at the same time. They serve their turn regardless, but occasionally, when blinking together, their combined brightness makes the darkness that follows darker.

Late in the play, Lear reunites with Gloucester, who has had his eyes torn out. It’s here that Coffee and Ferguson shine together. With Lear fully mad, Coffee is freer to play to his comedic strengths. As these men, blind to their offspring’s treachery, one now literally, rediscover each other, these two actors coax all the levels of tragedy and tenderness out of the encounter without wringing it out of shape. It’s as if they know that the blades of irony are sharpest when handled gently. By the end, no one escapes uncut.

THE WINTER'S TALE

directed by T.J. Walsh

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

youtube trailer: https://youtu.be/MBwlbeLE_pY

Trinity Shakespeare Festival navigates the difficulties of the late romance The Winter's Tale with finesse.

theaterjones.com

by M. Lance Lusk

In the latter part of his career, Shakespeare penned six plays—meditations on the dark night of the bittersweet soul—called the “romances.” These works are characterized by a blending of the comedic and tragic, truth through action, time gaps, miracles, the transformation of death into life, and hard-won reunions.

Of the six romances (Pericles, Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale, The Tempest, and The Two Noble Kinsmen), The Winter’s Tale is the most difficult to produce successfully because of its vastly different halves of tragedy and comedy taking place in far-flung locales, and disparate time changes. For these reasons, and many more, theaters tend to avoid The Winter’s Tale, especially during summer seasons that beg for lighter fare.

In Trinity Shakespeare Festival’s eight years of producing dual repertory plays, they had only attempted one romance, 2014’s visually insightful The Tempest (by far the most produced play in the genre). Taking on the challenge of The Winter’s Tale, with Founding Artistic Director T.J. Walsh at the helm and the returning Trisha Miller in the cast was one I looking forward to TSF attempting.

The first half of the play takes place in chilly, rigid Sicily (Clare DeVries’ set of somber blues and wooded winterscapes set the mood). King Leontes (J. Brent Alford) and his pregnant wife, Hermione (Allison Pistorius) entertain his childhood friend, King Polixenes (Richard Haratine). Leontes is suddenly struck with insane jealousy leading to deaths and exile that propel the play sixteen years in the future to Bohemia where Leontes’ lost daughter, Perdita (Amber Flores who shines in the musical numbers) finds folksy purchase in the home of an Old Shepherd (David Coffee) and his son, the Clown (Garret Storms).

It is a tribute to Alford’s skill that Leontes turn from bon vivant regent to raging tyrant (yet still sympathetic) is believable. Pirstorius has her hands full—and succeeds in—making a similarly difficult transformation from charming queen, to imprisoned martyr, to living statue (kudos to Walsh for handling the staging of the final reunion, and the famous “Exit pursued by a bear” scenes perfectly).

Haratine makes his snobbish Polixenes likable although he dislikes the union between his son, Florizel (a musically gifted Teddy Warren) and Perdita. Coffee and Storms make for a fabulous comedy pair, and Blake Hackler’s rascal conman Autolycus rounds out the action with more much-needed hilarity.

The play finds its steadfast conscience in the character of Paulina (Miller), a Sicilian Lady who stands up to Leontes, looks after Hermione, and facilitates the wronged queen’s “return.” It takes a supremely confident actor, like Miller, with a calm presence (think Judi Dench in the recent West End production in London) to make it work.

Lloyd Cracknell’s Jane Austen-style (Regency) costumes of gowns, frock coats and boots for the men, and the Bohemian Gypsy land of country St. Pauli Girls are all beautiful. Alan Shorter’s music supervision and Toby Jaguar Algya’s sound design keep the propulsive beats coming and highlight the gorgeous song and dance numbers (choreography by Kelsey Milbourn). Particularly moving is the cast’s celebratory rendition of Hillsong United’s “Relentless.”

Perhaps it is true that “a sad tale's best for winter,” but this Tale shines bright in any season.

measure for measure

directed by T.J. Walsh

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

criticalrant.com

by Alexandra Bonifield

T.J. Walsh directs Shakespeare with a defining, comprehensive understanding of the works and unwavering affection for them. He solves the challenges inherent in the so-called “Problem Plays” as if they are child’s games. Last year’s production of The Winter’s Tale, an odd mix of performance styles with a convoluted plot, hateful characters, a man eaten by a bear, a pastorale and the surreal transformation of a statue to life became a poignant love poem of redemption and reconciliation under Walsh’s tender, clearly delineated guidance. So it goes with this year’s production of the problematic Measure For Measure, bawdy comedy interwoven with examination of lust and power that rivals the savagery of David Mamet. With the same sterling cast from Richard III, Walsh balances the incongruities into a thought provoking, entertaining unity that reaffirms love, commitment, wise governance and the fun of tomfoolery. Life flows in endless samsara cycles. Richard Haratine excels at playing characters on odysseys or in search of personal illumination. His soulful Duke, wandering the countryside disguised as a simple friar in order to observe his established rule of law enforced by a zealot, functions intriguingly as the play’s deus ex machina and unexpected hero. Montgomery Sutton suffers silent torture of the damned as the “principled” zealot tripped up by his own humanity and abuse of power. His character Angelo is one of Shakespeare’s most despicable villains. Under Walsh’s direction Sutton’s Angelo undergoes a vivid trial of self-loathing for his grievous misdeeds, suffering the consequences with humility and dignified resignation. Angelic and composed, Kelsey Milbourn’s Isabella glides ultimately into true love with her bandied about virginity intact. “Some rise by sin, and some by virtue fall.” Propriety carries the day, which could become saccharine and boring if it weren’t for the marvelous clowns.

As foils to all the sad souls searching for Buddha-like transformation, Garret Storms as a scalawag dandy, David Coffee as a pimp named Bum, Sarah Rutan as the brothel madam, Richard Leaming as dissolute jailbird Barnardine and the enchantingly versatile Blake Hackler as witless constable “Elbow” conspire with madcap bawdiness and delicious comic timing to bring the audience’s attention back to solvable, silly earthly matters. Their endeavors reveal how humor can indeed function as best medicine for the soul…. The overwhelming cruelty of the character Angelo tends to dominate most productions of Measure For Measure. His issues and sins are egregious, but ultimately justice prevails. This Measure For Measure is a lively and loving, in balance production under Walsh’s guidance, pleasing to view with the resplendent Renaissance costumes procured by Lloyd Cracknell and under Michael Skinner’s soft, warm lighting. Almost the star of the production without uttering a word is scenic designer Will Turbyne (Resident Technical Director and Scenic and Lighting Designer at University of Dallas). He graces the production with a magnificent, oversized, slightly off kilter ornate church window through which projections of blue sky or lush gardens can be glimpsed, pulling the audience through the proscenium into the sometimes sanctimonious, sometimes scandalous, sometimes blessedly pure, environment and underscoring the mood of the play with vibrant physical dramatic effect.

Thank you, Trinity Shakespeare Festival, Directors T.J.Walsh, Stephen Brown-Fried and Managing Director Harry Parker for another brilliant pairing. I can’t wait until we celebrate your first decade in 2018.

romeo and juliet

directed by T.J. Walsh

TRINITY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL

Joullayne.com

Romeo and Juliet at the Trinity Shakespeare Festival is a play whose immovable backdrop is love. But its action is beautifully propelled by instigation and hatred, two necessary characteristics for trolling. The beauty of the play comes from our presuppositions that young, carefree lovers will almost certainly abandon trolling for the naïve prospect of a romantic unity. In a world of trolls, however, the naïve and the idealistic, no matter how pure at heart, are always victimized. Romeo (Quinn Moran) and Juliet (Carly Wheeler), whether from their growth-spurt as performers (they are both quite young and clearly fully of potential), with fantastic direction and coaching by T.J. Walsh, could not have been cast better. They brimmed with youngsters’ infatuation, which embarrasses onlookers, but only emboldens the two in love. They are so emboldened in fact, that, as Shakespeare wrote them and as Moran and Wheeler made them, the two denounce the animosity of the other characters, trolling them, instead, with hidden empathy. This was evident in Wheeler and Moran’s ability to build a springing gleefulness in their performances.

Perhaps this is the catharsis of Romeo and Juliet, the nobility of abandoning outrage for giddy bliss. Though the Montigue and Capulet crews offered admirable outrages to foil the lovers, Richie Haratine’s Friar Laurence drew us into the dangerous severity that even a balanced attempt at trolling can produce. I couldn’t help but note the chemistry that Haratine and Moran found with one another, almost like, forgive the pop-culture reference, that between Doc Brown and Marty McFly. Haratine ginned up a somber fondness from the audience with his version of the friar’s interest in his parishioners' contentment. It was palpable to the audience, and it was warm to experience his careful attention to a meaningful delivery. Unfortunately, his trolling efforts, a seemingly harmless concern for Romeo and Juliet’s well-being, devises too much complication. From it comes misunderstandings and distraught families. As the characters gather for the final mourning, Haratine has us feel the effect of Romeo and Juliet’s “tedious tale” because that, invariably, is all we get from our trolling.

There is hope here. There are lessons. Shakespeare’s trolls inform the audience that recanting behaviors and revealing true selves can turn aggressive desire into salvaged relationships. The Bard’s trolls also demonstrate the devastation of fulfilling the trollers’ ends. An honest discourse, rather than a disingenuous attempt to hobble an opponent, is the best way to prevail.

directing - EQUITY COMPANIES

Professional Directing, Equity Companies

"T.J. Walsh's direction and staging is bewitching, exhilarating, and marvelous all at once. Nothing is left out of this director's vision; everything is staged with soothing flow. Walsh's direction here is pure perfection." John Garcia, thecolumnonline.com

"T.J. Walsh's direction and staging is bewitching, exhilarating, and marvelous all at once. Nothing is left out of this director's vision; everything is staged with soothing flow. Walsh's direction here is pure perfection." John Garcia, thecolumnonline.com

METAMORPHOSES

directed by T.J. Walsh*

Theatre Three, Dallas, Texas

*Outstanding Direction Award - DFW Theatre Critics Circle

T.J. Walsh's direction and staging is bewitching, exhilarating, and marvelous all at once. Nothing is left out of this director's vision; everything is staged with soothing flow, like the waters within the pool that is built right smack in the middle of the stage. Walsh uses the water and stage like a kid at a candy store. Symbolism and subtext ebbs constantly from his direction. To create movement of time, Mt. Olympus, Hades, and earth he has the blocking flow peacefully from the emotions of the actors. The use of the pool and water is nothing short of pure brilliance. These two elements are used to under score emotion, to crate scenery, even to change an old woman into a young girl! Water symbolizes creation, cleansing, and the womb, which Walsh used to satisfying results. He uses subtle staging or movement to deliver so much character subtext or emotion within his direction. The pace never slacks or seems soporific. The actors devour the piece like a seven course meal, with the director wisely knowing when to really savor the moments, scenes, and emotions which come forth from Zimmerman's writing and her characters. On a side note, a special round of applause for Walsh casting roles non-traditionally. Walsh's direction here is pure perfection. John Garcia, thecolumnonline.com

* * * *

"Director T.J. Walsh has chosen a young cast that catches the play's every mood swing, from whimsical to majestic, from tragic back to satirical. By the time Eros walks onstage toward the end -- nude except for a fluffy pair of wings - for his rendezvous with Pscyhe, you are aught up in one of the most magical experiences in contemporary American theatre." Lawson Taitte, Dallas Morning News

* * * *

"The director, T.J. Walsh, employs his design elements wisely, from Tristan Decker's emotive lighting to the efficient set by Jack Alder. (Actors occasionally squeegee the set dry, during which Walsh inserts some clever stage business.) He imbues the storytelling with the style of a ballet -- elegant but visceral." Arnold Wayne Jones, Dallas Voice

* * * *

"The staging, directed by T.J. Walsh, doesn't disappoint. All in the ensemble have moments. One character says that "almost none of these stories have completely happy endings." There is, however, much depth, heart and even comedy. [This production] reclaims the seemingly lost theatrical art of storytelling." Mark Lowry, Fort Worth Star-Telegram

* * * *

"Yes, for its 45th season, themed around "the great storytellers," T3 seems to have discovered the fountain of youth with Metamorphoses, a fresh, sexy, lyrical production directed by T.J. Walsh and featuring a cast of talented eye candy drawn from a much younger pool than this theater typically dips into. There are new faces (and other body parts) on view. Word already has gotten out that this is a hot ticket. Metamorphoses is the best show of the summer so far, certainly the best work this theater has done in years." Elaine Liner, Dallas Observer

ROUNDING THIRD

directed by T.J. Walsh

THEATRE THREE, DALLAS

"Richard Dresser's delightful new comedy, Rounding Third, examines American notions of competition, parenting, friendship, love and grief through the eyes of two polar opposite coaches. The play's first North Texas staging has landed in Theatre Three's ballpark where director T.J. Walsh and two MVP caliber actors Doug Jackson and Jeffery Schmidt, belt a four-bagger." Perry Stewart, Fort Worth Star-Telegram

* * * *

"In Rounding Third, Richard Dresser's warm little comedy about baseball and friendship, two coaches -- one a veteran (Doug Jackson), one a newbie (Jeffrey Schmidt) -- watch their Chicago Little League team progress through a season. And we watch them watching baseball games we can't really see. Somehow it works, making for a winning play about wanting to win. This production has nice subtle work from the two actors under the direction of T.J. Walsh." Elaine Liner, Dallas Observer

the odd couple

directed by T.J. Walsh

THEATRE THREE, DALLAS

"The Odd Couple opened at Theatre Three on Monday under the direction of T.J. Walsh, who was responsible for Theatre Three's splendid Metamorphoses. This one, of course, requires two top bananas with oodles of comic gifts. Mr. Walsh has provided them in the persons of Doug Jackson as the grumpy slob Oscar Madison and Bob Hess as the prissy neatnik Felix Ungar. Both actors are equally accomplished at the broadest humor and the most natural realism, and they call on both styles here. In The Odd Couple the jokes are genuinely funny and still sound fresh after 40 years. The important thing here is that Mr. Jackson and Mr. Hess know how to sling the jokes and score with them. The production gets a lot of tis deluxe feel from the great supporting cast. They'll all leave you convinced that Mr. Simon knew best when he stayed lightest." Lawson Taitte, Dallas Morning News

* * * *

"The Odd Couple is now back in a sturdy, pleasant production at Theatre Three. Directed by T.J. Walsh, this Odd Couple gets its best laughs from the silences between Simon's punch lines. Doug Jackson (Oscar) and Bob Hess (Felix), their characters' friendship strained by Felix's obsessive-coompulsive tidiness, begen the second act with a 10-minute pantomimed war over personal boundaries. Oscar strides up and over thw furniture, kicking everything in his path. Felix tries to eat a plate of linguini, which Oscar heaves onto the wall. All a bit Niles v. Frasier Crane, but masterfully staged and acted. Simon says, see it again if you need to laugh it out for a few hours." Elaine Liner, Dallas Observer

CRIMES OF THE HEART

directed by T.J. Walsh

CIRCLE THEATRE, FORT WORTH

'CRIMES' BELLES CHARM

Crowd-pleaser has brains and heart

Dallas Morning News

by Manuel Mendoza

Crimes of the Heart is an evergreen. WIth its just-right blend of dramatic tension, humor and poignancy, Beth Henley's Pulitzer-Prize-winning play is a showcase for young actresses. Jenae M. Yerger, Trisha Miller and Dana Schultes -- all making their Circle Theatre debuts under the crisp direction of T.J. Walsh -- show why the SMU-trained Ms. Henley's 1979 play is so audience-friendly. Their demonstrative Magrath sisters, post-feminist takeoffs on the Southern belle, are impossible to resist.

Ms. Yerger, in the most nuanced part, does wonders with youngest sibling Babe Botrelle, who's been arrested for shooting her prominent lawyer-politician husband when the action opens. For two hours, she peels back Babe's hidden layers of strength and will, creating a complete human being from what initially looks like a ditz. With Babe in trouble, middle sister Meg (Ms. Schultes) rushes home from Los Angeles, where she's been struggling to launch a singing career. The comely popular girl for whom everything always came easy, she pays a price for daring to leave the familiar bosom of Hazlehurst, Mississippi. They come together at their sick grandfather's house, where lonely heart Lenny Magrath (Ms. Miller) is celebrating her 30th birthday alone. The drama is immediately leavened as Lenny repeatedly rams a candle into a cookie so she can make a wish.

Set in 1974, Ms. Henley, a Mississippi native, knows how to put words in these Southern women's mouths. Her dialogue is convincingly naturalistic, and director Mr. Walsh and his actresses make the most of the writer's gift for close observation. For long stretches, you can forget you're watching a play because the exchanges seems so real. Crimes is about how the Magraths come to terms with their baggage and their conflicts during Babe's hour of need. It's a crowd-pleaser, certainly, but one with brains as well as heart.

Babe's lawyer and potential love interest (David Fluitt) is a winning character in his own right, a combination of goofy smarts and boyish naivete. Ms. Schultes, in the least showy role, has a crackling scene with Mr. Fluitt when he first arrives to take the case. As we get to know Meg, Ms. Shultes bring her melancholy to the fore. And th gangly Ms. Miller, too attractive to be playing the old maid, pulls it off with a wide-eyed take on the possibilities of overcoming obstacles, even Lenny's shrunken ovary.

the retreat from moscow

directed by T.J. Walsh

CIRCLE THEATRE, FORT WORTH

'MOSCOW' A GOOD DESTINATION

Circle Theatre gives regional premiere to precisely built drama

Dallas Morning News

by Lawson Taitte

A taste for the literary doesn't necessarily keep a play from resonating emotionally. In the case of The Retreat from Moscow, it's quite the contrary.

William Nicholson's drama about a failing marriage, which Circle Theatre is giving its regional premiere, is constructed with lapidary precision. Mostly the three characters talk two by two, just like in a Greek tragedy. In place of a chorus spouting a verse commentary on the actions, it's the characters who quote poetry.

The device doesn't seem precious because the wife, Alice (Elizabeth Rothan), is compiling a poetic anthology and has a reputation for memorizing. Her youthful brilliance, even her love of verse, attracted her husband, Edward (Gary Moody), 30 years ago. Now, however, Alice constantly picks at Edward, creating scenes even in public. He hides behind the history books he teaches from, another source of metaphors and parallels. One about the disastrous end of Napoleon's Russian invasion gives the play its name, in fact.

The parents manipulate and communicate through their grown son, Jamie (Bill Sebastian). Psychologists would call the process triangulation -- pulling a third party into a relationship as a buffer. Jamie identifies with both parents, which makes his position all the more difficult.

Bill Newberry's set and John Leach's lighting create a suitably poetic environment for the three actors to work in. Under T.J. Walsh's direction, they admirably bring off the challenging script.

Mr. Moody feels just right as the unambitious, unpretentious man exhausted by his wife's constant criticism A reticent character often becomes a cipher, but not here. Ms. Rothan gets the showiest role, and she's best at its most intense moments. At the beginning, she works a little too hard at the mannerisms and the accent. But there's no one else around who could give us so much of Alice's grief and anger. Mr. Sebastian fits comfortably in the scenes with the father and rises beautifully to the play's final scene, which sums up the curiously moving family drama.

DEFIANCE

directed by T.J. Walsh*

THEATRE THREE, DALLAS

*Outstanding Direction Award, DFW Theatre Critics Circle

'DEFIANCE' intellegently delves into military moral dilemma

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

by Mark Lowry

In the first two of John Patrick Shanley's plays in the projected trilogy, Doubt and Defiance, the playwright tackles profound moral questions about once-unassailable institutions. Defiance, which opened in an astutely acted production at Theatre Three on Monday, it's the U.S. military during the Vietnam War. The story could easily unfold in court-room-movie-of-the-week style, but Shanley is too smart for that. The audience knows just enough to stay on seat's edge.

Directed by T.J. Walsh, Bryan Pitts, David Fluitt and Drew Wall give stirring performances. Steven Pounders as Lt. Col. Littlefield creates a likeable human out of a stern military ladder-climber and hero whom others are afraid to challenge. We also honestly believe his is head-over-heels for his wife. Speaking of which, Diane Worman as Margaret Littlefield might be the star here. She gives us a smart woman whose heart-breaking final scene drives home what has already be a riveting production.

directing - tcu

Productions directed at Texas Christian University

the diviners

directed by T.J. Walsh

Buschman Theatre, TCU

a youtube look at the "drowning" scene from our production of The Diviners.

https://youtu.be/8uTfQ00_j44

a video trailer from The Diviners at TCU

https://youtu.be/mLYTQmm_-kI

a youtube look at our production of The Diviners

https://youtu.be/8uTfQ00_j44

tom kellogg in b flat

directed by T.J. Walsh

Hays Theatre, TCU

A youtube look at the TCU Production: https://youtu.be/R405cT2an6U

In this touching and very funny comedy prequel to Melrose Stories we see young Tom Kellogg living in his San Francisco flat in the 1980s trying to sort out the complexities that have become his life. The play is four different scenes set in Tom's flat leading to major decisions in his life.

In the first story A PAS DE DEUX IN REMEMBRANCE we see Tom having to contend with a former lover, Jane, a dancer for the San Francisco Ballet, whom he still loves. In the second story A SEMINAR IN B FLAT, we find a graduate student from Columbia University who shows up for an early morning interview with Tom about his books but she really is more interested in his private life (and Jane) that are suggested in his books. In the third story AT RISE, we find Tom awake at 3am being confronted by his live-in girlfriend, Irene, an actress who is starring in a new play he has written, who is up and reading one of his books that happens to be about Jane. And finally in the fourth play, MAKE BELIEVE BALLROOM, Tom has a comic but moving heart-to-heart with his best friend, Joe, about the women in his life and his next step - to head out to New York City (where Jane has moved).

This is a funny and touching comedy. The four plays work brilliantly as an evening or each can stand up as a one-act of their own.

Single Set

5 Characters

3 women, 2 men

GUYS AND DOLLS

directed by T.J. Walsh

Scott Theatre, Fort Worth

a video short from Guys and Dolls at TCU

https://youtu.be/UroqZLCi1C0

HOLIDAY

directed by T.J. Walsh

Buschman Theatre, TCU

A youtube short - end of Act Two - "I love the boy, Neddy":

https://youtu.be/Qmzyugy2YFo

A video of the TCU production:

https://youtu.be/mTnoPi2LN_Y

A youtube short of Holiday production at TCU:

https://youtu.be/aRbTTeMbAps

born on a sunday

directed by T.J Walsh

Hays Theatre, TCU

BORN ON A SUNDAY by T.J. Walsh

Theater Review: Proving August Strindberg’s Greatness

D Magazine

By M. Lance Lusk Published in Arts & Entertainment

I am always saying I would like to see more plays by August Strindberg. His experiments in expressionist and surrealist techniques and dream-like Scandinavian moodiness are beyond intoxicating to this critic. Now, the chance to see an original work about that incomparable Swede, done in his distinctive style by an incredible director and playwright was a theatrical blessing. Theatre TCU presents Born on a Sunday written and directed by T.J. Walsh.

There is a reason Eugene O’Neill referred to Strindberg in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech as “that greatest genius of all modern dramatists.” He was an exceedingly prolific polymath playwright, poet, essayist, novelist, painter, and dabbler in the sciences. However, he experienced a tumultuous time of psychotic attacks, paranoia, delusions, and religious turmoil while he was abroad in Paris in the 1890s called the “Inferno crisis.”

The program notes inform the audience that much of what we are seeing is “true…the rest is imagination.” And that is the special genius of Walsh’s play, that investigation of this crucial time in Strindberg’s life seen through a speculative lens that resembles his visionary experiences that straddle the real and dream worlds. From Brian Clinnin’s whimsical, bridge-like set of wood beams, rivets, curves, and elevated platforms, to the clear, fantastical, and chilling sound design and composition, and lights by Chris Hassler and Jim Rogers respectively, to Yuheng Dai’s luxurious period frock coats, gowns, and Victorian-inspired dance outfits this is a play that sets a definite mood of history and reverie.

Walsh, an Associate Professor of Theatre at TCU, is also the co-founder and Artistic Director of the excellent Trinity Shakespeare Festival. Born on a Sunday is an amazing accomplishment in and of itself, but the fact that Walsh is able to fashion a production of such superior quality with non-professional actors in training is mind blowing. They handle this difficult and unconventional material with artistic ease.

Standouts from this excellent ensemble include Bradley Gosnell as the tortured Strindberg, Gabriel Whitehurst as Dr. Horatio Christensen, the Danish psychologist who befriends and treats the playwright with hypnosis, and Shae Lynn Goldston as a fiery feminist doctor in love with Horatio. A special note of recognition too for the sylphlike Furies/Muses (Marisa Bonahoom, Caroline Iliff, Jackie Raye, Abbie Ruff, Lexie Showalter, Kelsey Summers, and Zach Gamet as The Power) who plague and inspire Strindberg. Choreography by Penny Ayn Maas contributes to this chilling ballet of intertwined and inspired madness.

Strindberg craving fulfilled.

VOLLEYGIRLS

directed by T.J. Walsh

Hays Theatre, TCU

youtube short - curtain call

https://youtu.be/-oAKV_hRmbU

youtube video of production

https://youtu.be/A6hwOL3O1eQ

youtube trailer of Volleygirls at TCU

https://youtu.be/T2Fr4M002WY

youtube short video of TCU production

https://youtu.be/rPRng7Ac23I

The trials and tribulations of a high school volleyball team heading toward winning district. "Funny and touching and very true."

the house of blue leaves

directed by T.J. Walsh

Buschman Theatre, TCU

a youtube short - "end of play" from the TCU production:

https://youtu.be/dQi62g7gaCY

a youtube short - "four corners" from the TCU Production:

https://youtu.be/omTzycfNNxM

a youtube look at the TCU production of The House of Blue Leaves

https://youtu.be/b_zApG-XCqI

a look at Artie's prologue of The House of Blue Leaves at TCU

https://youtu.be/zPKUDFWbYJk

"At once dark and zany, House is one of Guare's most powerful works, presenting timeless, dramatic themes – the power of celebrity, the desire for fame, and the longing to escape to a better life – in a screwball comedy plot."

URINETOWN

directed by T.J. Walsh

Buschman Theatre, TCU

a video short from Urinetown at TCU

https://youtu.be/J9BpriomSqg

"URINETOWN is a hilarious and resonating tale of greed, corruption, love, and revolution in a time when water is worth its weight in gold. It is a social and political satire set in a fictional future where a terrible 20-year drought has crippled the city's water supplies."

our town

directed by T.J. Walsh

Buschman Theatre, TCU

a youtube slideshow look of TCU's production of Our Town

https://youtu.be/49zTVxOdWDA

a brief youtube look at a Sunday rehearsal of Our Town

https://youtu.be/zatAZerp2CA

a trailer for OUR TOWN - read thru

https://youtu.be/LSwLP2sgnkk

hamlet

directed by T.J. Walsh

Hays Theatre, TCU

a short - "method to his madness" scene from the TCU production: https://youtu.be/SgtQfAiTeZQ

a look at the TCU Production: https://vimeo.com/815897030

getting out

directed by T.J. Walsh

Hays Theatre, TCU

W A T C H:

youtube short "the closing" from TCU production

https://youtu.be/7OwtKmB1qrM

video short from Getting Out at TCU

https://youtu.be/AodvjYkogzk

"Getting Out is a remarkable play about an ex-convict — but looking back, it also feels like a watershed moment in the history of plays about and by women."

misalliance

directed by T.J. Walsh

Buschman Theatre, TCU

a youtube short from the TCU production: https://youtu.be/7JBJxihXeIY

a youtube video of the TCU Production: https://youtu.be/svDivnkRFdA

"Shaw at his height - witty, insightful and just fun."

the glass menagerie

directed by T.J. Walsh

Hays Theatre, TCU

a youtube short from the TCU production: https://youtu.be/MNDGpbdybmE

a youtube slideshow look at TCU's producton of The Glass Menagerie

https://youtu.be/zu8w1uvo1OE

book of days

directed by T.J. Walsh

Hays Theatre, TCU

melrose stories

Short from the TCU Production: https://youtu.be/YAx4PDx38HY

A video of the TCU Production: https://youtu.be/hjfmeGCygg8

MELROSE STORIES by T.J. Walsh

TCU's 'Stories' has happy ending in this romantic comedy

LOVE AND LAUGHS CONQUER ALL OBSTACLES IN ADVENTUROUS COMEDY

Dallas Morning News

by Lawson Taitte, Theatre Critic

Melrose Stories has two strikes against it, right from the start. The hero narrates the story by talking to the audience. A lot. And the character is a writer - seldom a good sign.

But no inning is over until the final out, and playwright T.J. Walsh keeps swinging hard and gets a hit - maybe not a home run but definitely a triple.

Texas Christian University, where Mr. Walsh teaches, gave Melrose Stories its world premiere Wednesday under the playwright's direction. This romantic comedy dares a lot. Its tone ranges from sitcom humor to a magical ending right out of Jacobean romance. And it baldly lets you know it's doing just that. A beneficent ghost wanders through the action, and the plot involves a big secret. (The savvy will guess it immediately, yet the answer still feels unprepared for when it comes out - just as Mr. Walsh planned.)

The action mostly takes place in a Los Angeles bookstore, though it also wanders freely through space and time. The narrator, a New York novelist named T.D. Kellogg (Clint Gage), has been suffering from writer's block for more than a decade after his successful debut. His aunt (Katie O'Brien) dies and leaves him her heavily mortgaged store. T.D. falls in love with the place, the staff and - in a romantic way - the manager, Rose (Michelle Martinez).

The scenes in the store do feel a lot like high-quality TV comedy, with the employees and regulars trading quips and exuding hormones. Mr. Walsh halts objections by having the funny guy, Walter (C.J. Meeks), quarrel endlessly with Wilma (Jaclyn Napier), a feminist grad student who's writing her thesis on sitcoms.

Mr. Walsh has looked past recent romantic comedies for models and gone straight to the top. The juxtaposition of low popular humor with serious characters and situations feels Shakespearean, in a nicely unpretentious way. The laughs are there, and the deeper emotions as well.

Perhaps the mystical happy ending doesn't have quite the tearful payoff it should - but it could just be that the student actors aren't always the right age or in possession of enough technique to make the improbable convincing.

A number of cast members are outstanding anyway. Ms. O'Brien radiates the right kind of hopeful aura, Mr. Meeks is hilarious, and Scott Rickels as the gay store employee has a nice offhand charm.

Melrose Stories is a real contribution to the vanishing genre of romantic comedy.

on the town

directed by T.J. Walsh

Ed Landreth Auditorium, TCU

12 ANGRY MEN - 12 ANGRY WOMEN

directed by T.J. Walsh

Hays Theatre, TCU

A youtube slideshow of the TCU Production

https://youtu.be/B83ZlVNNJ0U

Ah, wilderness!

directed by T.J. Walsh

Buschman Theatre, TCU

SCHOLARSHIP

Research interest in the history and theory of Authorship

Nominee:

2022 College of Fine Arts - University Deans’ Teaching Award

2018 College of Fine Arts - University Distinguished Achievement as a Creative Teacher and Scholar Award

2016 College of Fine Arts - University Distinguished Achievement as a Creative Teacher and Scholar Award